In questo breve articolo vorrei mettere a confronto alcuni termini francesi in un triangolo linguistico: francese, italiano e inglese.

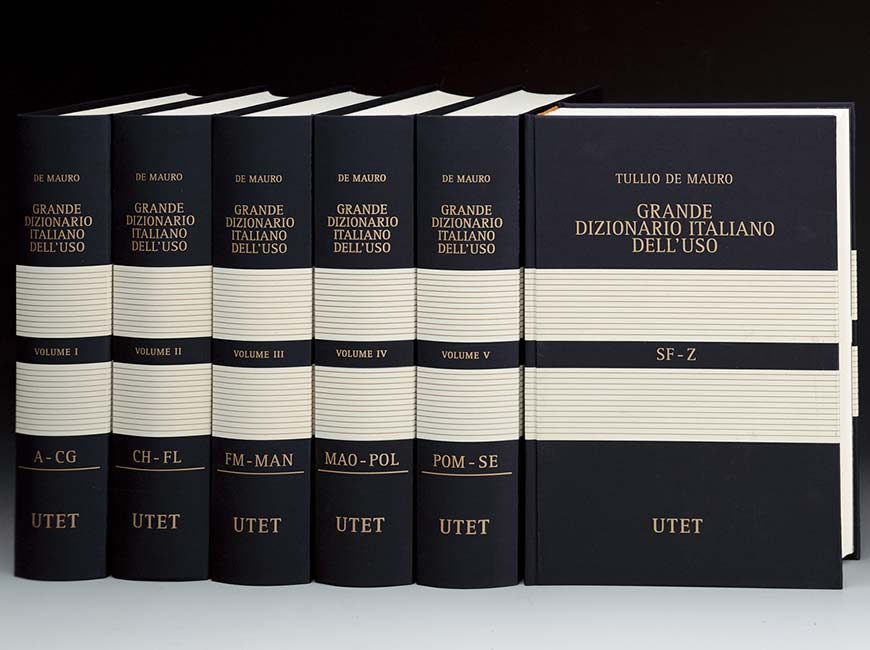

Vorrei dunque cercare di far luce su alcuni termini che secondo alcuni dizionari e opere di consultazione non sempre sono vere parole francesi.

Partirei con chiffonnier. Questo termine che descrive un piccolo mobile appare sia in italiano che in inglese. Tuttavia in italiano sembra esistere una variante al femminile, chiffonnière. Boch asserisce che si tratta di un italianismo. Alcuni dizionari (Treccani e Zingarelli) la riportano ma la etichettano come parola antica o rara. Opterei per mantenere l’originale maschile. Da notare che in America del Nord, per chiffonnier si intende un mobile più grande a volte provvisto di specchi.

Un altro termine che vale la pena rivedere è bohémien . In italiano sembra prevalere il senso di un artista libero e anticonformista (e forse squattrinato). In francese però, il termine è sinonimo di zingaro o vagabondo. L’inglese propende per il significato italiano seppure Merriam Webster riporti anche il senso di Romani, ossia rom o gitano.

Alcune parole italiane hanno l’aspetto francese ma non hanno nulla a che vedere in quanto sono degli pseudocalchi: pan carré (pain de mie, sliced bread) ne è un esempio. Così come frappè, che sembra essere una troncatura di frappé par la gelée. Termine non usato in francese se non, forse, per riferirsi al lait frappé (termine franco-canadese per tradurre milkshake) oppure allo champagne frappé, pratica tra l’altro non consigliabile. Ma qui divaghiamo. Va detto che, in inglese, frappé è un termine regionale del New England per descrivere appunto il lait frappé mischiato al gelato e che tra l’altro ha dato origine al neologismo sincretico frappuccino (frappè e cappuccino), originario per l’appunto del Massachusetts. Insomma, i francesi questo frappè non sembrano conoscerlo proprio.

Décolletage fornisce un ultimo esempio di francesismo storpiato. Stranamente in inglese questo termine è sinonimo di décolleté quando usato come sostantivo. In francese, invece, questo senso del termine sta al massimo a indicare l’azione di tagliare la stoffa di un abito per metterne a nudo il collo. Non quindi l’effetto sortito da un abito con una scollatura evidente.

Occhio quindi a non scollarsi troppo dal significato originale dei termini francesi per non attrarre la stessa attenzione di un abito troppo décolleté.