Ever noticed how the Italian word intervento can range across countless semantic fields? It is definitely one of those pesky words that translators from the Italian often end up at loggerheads with.

Here are some of the semantic fields in which intervento appears in Italian. As you can notice, the first few examples overlap with their English counterparts.

- intervento in politics, such as American intervention or military or police intervention = intervento americano, intervento della polizia, intervento militare.

- intervento in the medical field, a surgical intervention, though surgery is perhaps more common = intervento chirurgico.

- intervento in the religious sphere, divine intervention = intervento divino.

- in law, intervention and intervento also seem to mean the same thing.

Interestingly, in English some of these collocations can be quite strong as in ‘surgical intervention’, which helps clarify what kind of intervention we’re talking about. By contrast, Italian simply uses ‘intervento’ to refer to a medical procedure that often requires surgery, while allowing the listener to infer its precise meaning from context.

We then move on to that kind of intervento that seems to be more widespread in Italian than in English.

- Architectural intervention, though found in specialized journals and magazines, is not half as common as the ubiquitous intervento architettonico.

Before coming to a greater rift between the two languages, where:

- Intervento di restauro o di manutenzione is definitely not an intervention here. Perhaps maintenance work, renovation work or conservation work. Interventive conservation does, however, exist. Which should not be confused with conservative intervention, a medical term.

- Intervento musicale = a klutzy phrase that has no direct equivalent in English. A musical performance? Interlude or intermezzo definitely sound much better, though they differ somewhat from what Italian speakers mean by ‘intervento musicale’.

- intervento (correttivo) for correcting something: a correction, a remark, a comment.

- intervento (accademico): this could range from presenting a paper at a conference to any speech or written contribution.

- intervento tecnico = service or technical service

Finally, a couple of instances where the meaning of intervento is closer to response:

- pronto intervento = emergency response

- tempi d’intervento = response time

Similarly, the English verb intervene occasionally behaves somewhat differently than its Italian counterpart. Sentences like intervenire a un congresso simply means to ‘speak or be a speaker at a conference’. And ringraziare gli intervenuti ( a noun derived from the participle) is to thank the speakers or participants. By the same token, a sentence like five months intervened between the outbreak and the end of the epidemic is probably best rendered as intercorrere.

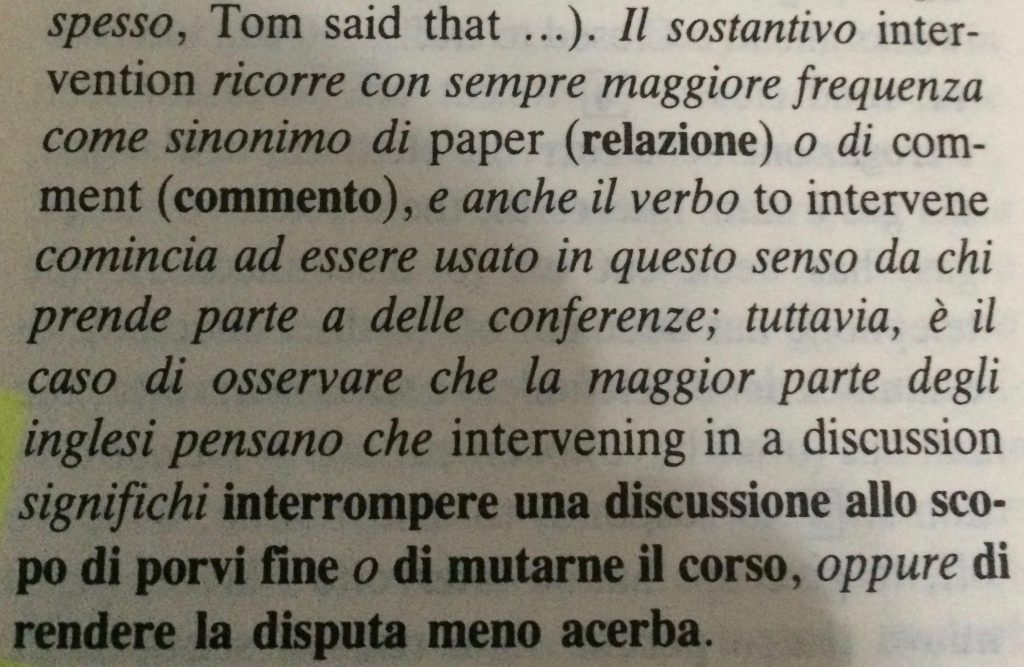

On a final note, with regard to intervento accademico or intervento a una conferenza,Virginia Browne’s otherwise excellent 1987 edition Odd Pairs and False Friends reads that:

You will forgive me for intervening, but I wouldn’t go that far.