Bookstores – both online and of the brick-and-mortar kind – are chock-full of reference books on grammar. vocabulary, idioms and proverbs. These books and dictionaries tend to illustrate their meaning or – in their bilingual versions – compare or contrast commonalities between languages or, at best, they might contemplate the false cognates that trip up language learners and translators alike. Or they might find similar idioms in the receiving culture. I find it, however, far more fascinating to seek out those idioms, words or concepts that are seemingly untranslatable and that shed some precious light on how a certain culture thinks and expresses itself.

This is of course a wide-reaching area in translation studies and one that cannot be neatly organized since lexical gaps in a given language become conspicuous especially during the translation process.

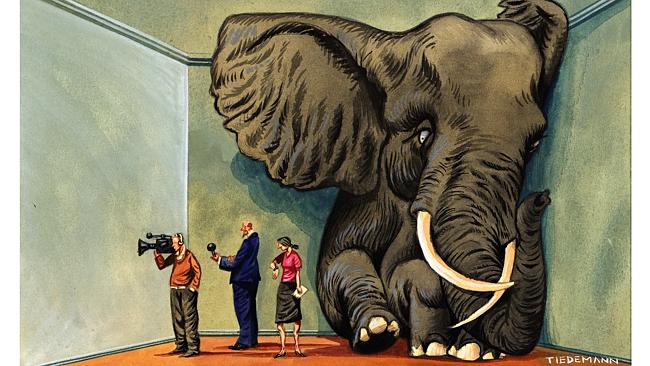

For instance, some American or English idioms simply don’t exist in Italian. One of my favorites is the elephant in the room, which is a fairly recent coinage. It has now become widespread across the English-speaking world, but it seems other languages lack this idea. Italian does have il convitato di pietra, but it refers more to an ominous presence rather than a problem no one wants to address. Close, but no cigar, I suppose.

Similarly, I find it peculiar that a coffee-imbued culture like Italy does not seem to have a concept like the American (via the now outdated German) kaffeeklatsch. The Swedes have fika, the Danes and Norwegians kaffeslabberas. It appears that Italian can’t stretch beyond a simple caffè. I guess ‘Prendiamo un caffè?’ already carries the same implications.

What about roadkill? Why hasn’t anyone come up with something niftier than carcassa di animale investito? Is Italian less flexible than English in creating words and concepts?

On the other hand, why does Italian go out of its way to come up with consuocero (son’s or daughter’s father-in-law), but draws no distinction between nephew/niece and grandson/granddaughter, both being nipote. Pretty odd for a family-oriented culture.

And speaking of odd, the Dutch must have some of the wackiest expressions in Europe. Een waarheid als een koe (literally a truth like a cow) is a self-evident truth, a truism, which can of course be paraphrased quite easily, though a translator can’t help but wonder why this idiom has come into being. (We know how, but not why.)

The Danes (and the Norwegians) also offer plenty of zany idioms whose origins seem to have been lost to time. And at skyde papegøjen – it is safe to say – could easily take the cake as far as I am concerned. Meaning literally ‘to shoot the parrot’, it means to be extremely lucky or to have hit the jackpot. The origin of this expression dates back to 13th-century France but, to the best of my knowledge, the French have since decided to leave their perroquets alone.