Language shapes culture and – contrariwise – culture shapes language. Although this may sound like a cliché, translators are often faced with imbecilically clichéd words that are just the brainchild of imbecilic behaviors in society. Mind you, a word in itself is never imbecilic, but it has the power to call forth the most invidious emotions in a churlish translator like me.

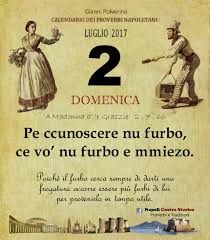

This is the case with the Italian word furbetti, which can certainly drive an otherwise unruffled translator into a frenzied spate of choleric outbursts. Furbetti is so ingrained in Italian culture and media that Italian readers may have been numbed by its widespread use across various collocational patterns. These include: i furbetti del cartellino; i furbetti del reddito di cittadinanza; i furbetti del quartierino; i furbetti delle targhe estere; i furbetti della tassa di soggiorno, etc.

As a catchall, i furbetti are those who seemingly find all sorts of loopholes to advance in life by outsmarting the system without having to shoulder the burden other law-abiding citizens are normally expected to. Examples could range from jumping the line at a ticket booth to dodging taxes. A federal or national crime in most countries.

It is thus most infuriating that the Italian media often resort to this cutsey patootsey term to label what other languages would simply identify as crime-prone individuals to put it mildly. Outright criminals in my book.

The same term furbetto can be used in Italian to describe a naughty child, what the English would call a cheeky monkey and the Americans a little brat. A birbante is another word used in this way. So how can such a harmless term of endearment be used so frequently and nonchalantly to refer to criminal, or in any case, offending, behaviors?

It has always baffled me that the media seem to encourage this behavior or deflate the seriousness of the charges by letting these offenders get off lightly and by camouflaging the truth with what is tantamount to a verbal pat on the shoulder.

Language is a powerful tool that permeates the mind – oftentimes surreptitiously. Translation – precisely through the lack of direct equivalents in other languages – can shine a light on these aberrant and abhorrent practices and call writers and linguists to task when tongue-in-cheek is uncalled-for.

The churlish translator is therefore hopeful that the baby talk will be thrown out with the bathwater once and for all to make room for adult talk.